By Ermias Hailu

Following to the end of the second world war Egypt’s failure to integrate Eritrea to its territories, due to Emperor Haile Selassie’s superior diplomatic skills, the then Pan- Arab nationalistic President Nasser’s government turned to ethnic and religious subversion against Ethiopia. In 1955 Egypt began working for the instigation of an “Arab” revolution in the then autonomous Ethiopian province Eritrea, to that effect, hundreds of young Muslims from Eritrea, were invited to Cairo to study and enjoy special benefits. Although they were not native Arabic speakers, they absorbed the spirit of Arab revolution and adopted a modern Arab identity. There they also learned how to set up a modern guerrilla ‘liberation front’ and by 1959 they had finalised their training in Egypt and were ready to establish the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) and they returned to the Sudanese town of Kassala and become connected to the pro- Egypt Sudanese Al-Mirghaniyya movement. More concretely the ELF launched an open anti-Ethiopian revolt in Eritrea in 1961, claiming and propagating a fake Arab Eritrean identity.

“The Arabism of Eritrean People” remained one slogan of Nasserism to its end and to promote Eritrea’s liberation from Ethiopia, Nasser was also ready to help local Eritrean Christian Tigrians who resisted reunification with Ethiopia. In 1955, the prominent leader of Christian Tigreans in Eritrea, WaldeAb WeldeMariam, was invited to broadcast daily anti-Ethiopian propaganda on Radio Cairo and the Nasserist regime remained the main pillar of support for the Eritrean separatist movement until 1963. The myth of Eritrea’s Arabism, adopted and advanced by Eritrean Muslims, was to survive until 1980’s and the war in Eritrea that was instigated by Egypt lasted 30 years and caused untold human and financial loss both to Ethiopia and Eritrea. As of today, Eritrea is a de facto colony of Egypt and is being utilised as a proxy war front against Ethiopia and it is also the command post of those Ethiopian political groups who opted to ally with Egypt. Hundreds of Eritreans’ industries, hardworking and proud citizens and their children escape the prison and pariah government of Eritrea on daily basis facing any risk on their way.

No less significant was the issue of Nasserist influence on the Somali nationalists and beginning in the mid-1950s Nasserist policy, literature, and agents worked to enhance the anti-Ethiopian dimension of Somali nationalism branded it as “Greater Somalia”. The Somalis encouraged by the potential Egypt backing, claimed about one-third of Ethiopia’s territory and when they united and received their independence in July 1960 and joined the Arab League 1974, they continued to present a serious on-going challenge (two wars fought) to the integrity of the Ethiopian sovereignty until Somalia was disintegrated and engulfed by civil war in 1991. The disintegration of Somalia which has caused the scatter of Somalis throughout the world and death of millions of Somalis by war and famine and wastage of decades of nation building opportunity was a byproduct of the failed Egyptians destabilisation strategy of Ethiopia.

Similarly, after Egypt failed to stop the British from allowing Sudan to declare its independence from Egypt in 1956, it has been constantly interfering into the internal affairs of Sudan including the Sudanese army staged coup d’état in November 1958, overthrowing the civilian government of Abdullah Khalil which had uncompromised and hard negotiation position on the Nile river, in which Egypt friendly Gen. Ibrahim Abboud led the new military government.

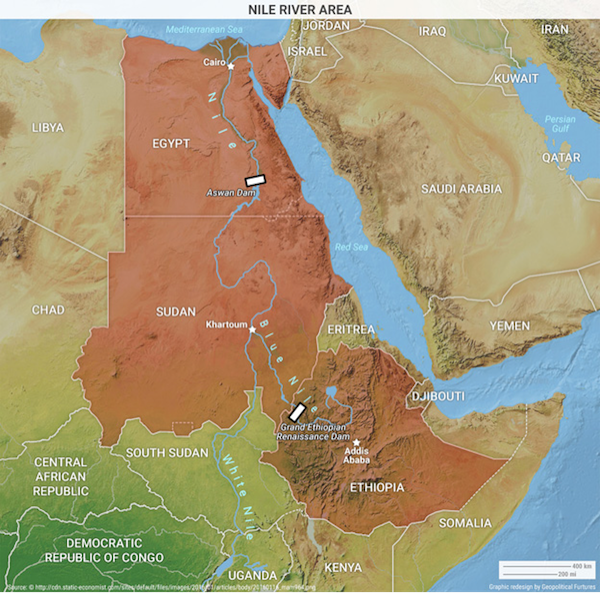

The 1959 Nile water share agreement signed between Egypt and Sudan which gave the lion share to Egypt (78% to Egypt and 22% to Sudan on the net annual flow after deducting 10 billion cubic meters for evaporation loss) was agreed with Gen Abboud. Considering the fact that, the flow measuring point is deep in Egypt at the Aswan High dam and the annual hypothetical evaporation loss of 10 billion cubic meters, the share for Sudan is substantially lower than 22%. If the water share allocation was done taking into account “population size and arable land area” as factors, Sudan’s share should have been not less than 40%.

Though Egypt opposed the split of South Sudan from Sudan during the pre-independence conflict time, currently it is the main sponsor of the fragile and corrupt President Kiir government and is prolonging the suffering of the South Sudan people with the objective of getting a foothold near to Ethiopian border to sabotage Ethiopia.

We are also hearing saber-rattling of few bribed government officials from South Sudan and Uganda trying to finger point at Ethiopia in relation to its decision to build the GERD and the speedy ratification of the “The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement” by its parliament.

The Zero-Sum game that has been played by Egypt to ensure its water security has become unsustainable, out of dated and irrelevant (it is a myth) for the following reasons:

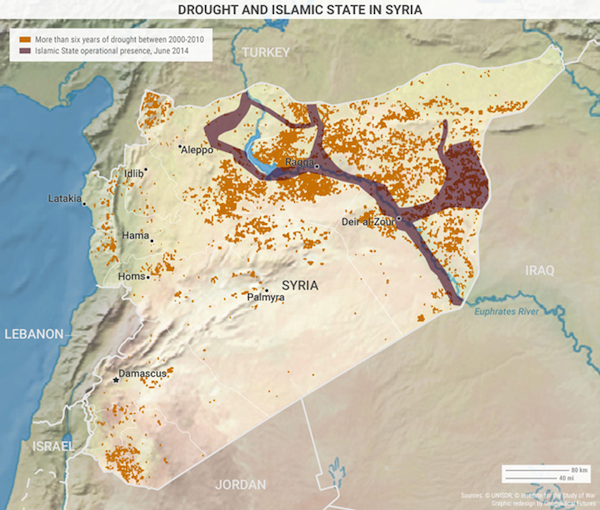

Creating jobs and feeding the rapidly growing population in the Horn of Africa and in the countries of the Nile Basin demands governments to generate power for industrialisation and mechanised farming and produce sufficient food to ensure food security which requires more consumption of water. The domestic consumption of water also increases in proportion to the population growth.

Creating jobs and feeding the rapidly growing population in the Horn of Africa and in the countries of the Nile Basin demands governments to generate power for industrialisation and mechanised farming and produce sufficient food to ensure food security which requires more consumption of water. The domestic consumption of water also increases in proportion to the population growth.

The Aswan High dam only stores one year flow of the Nile water, whereas, global warming and other unpredictable climate changes could result in a drought that lasts to the biblical-proportion of up to seven years. In that case, the Aswan dam could dry with unimaginable consequences on Egypt’s 94 million growing population and makes Egypt’s water security strategy null and void.

The Aswan High dam only stores one year flow of the Nile water, whereas, global warming and other unpredictable climate changes could result in a drought that lasts to the biblical-proportion of up to seven years. In that case, the Aswan dam could dry with unimaginable consequences on Egypt’s 94 million growing population and makes Egypt’s water security strategy null and void.

The growing population of Egypt also requires more water than the storage capacity of the High Aswan dam. That necessitates the construction of additional reservoir dams either in Ethiopia and/or Sudan (building an additional dam in Egypt looks not practical).

The growing population of Egypt also requires more water than the storage capacity of the High Aswan dam. That necessitates the construction of additional reservoir dams either in Ethiopia and/or Sudan (building an additional dam in Egypt looks not practical).

The Aswan high dam may be filled by silt within the next 300 to 500 years. How will Egypt manage such unavoidable fact with a huge population that is 95% dependent on the Nile water?

The Aswan high dam may be filled by silt within the next 300 to 500 years. How will Egypt manage such unavoidable fact with a huge population that is 95% dependent on the Nile water?

Considering the above points, it is expected that Egyptian water security strategists and the Egyptians government covertly want the construction of more dams in Sudan and Ethiopia as far as their historical share is not significantly affected. They also know that dams built in Ethiopia along the deep Abbay River Gorge could only be mainly used for hydroelectric power generation with lower evaporation loss and lower construction cost per volume. Egyptians are also considering others sources of water such us linking the Congo River with the White Nile and digging the Jonglei Canal in South Sudan which is good ideas but difficult to implement.

Then what is the reason that Egypt has been too nervous and trying to destabilise Ethiopia and sabotage the completion of the Great Ethiopian Renaissance dam(GERD)?

The following could be the main reasons:

Fear of the unknown which is a natural reaction considering the historical facts and the strategic importance of the Nile to Egypt’s future survival

Fear of the unknown which is a natural reaction considering the historical facts and the strategic importance of the Nile to Egypt’s future survival

Fear that Sudan (the potential main Nile water consumer) could use more than its agreed share of the 1959 agreement. This fear is reasonable as any dam built in Ethiopia will regulate the seasonal flow of water in Sudan which will enable Sudan to access more and steady flow of water year-round. This may call for a new Nile water share agreement between the two countries and I do not think Sudan will allow itself to be manipulated by Egypt for the second time.

Fear that Sudan (the potential main Nile water consumer) could use more than its agreed share of the 1959 agreement. This fear is reasonable as any dam built in Ethiopia will regulate the seasonal flow of water in Sudan which will enable Sudan to access more and steady flow of water year-round. This may call for a new Nile water share agreement between the two countries and I do not think Sudan will allow itself to be manipulated by Egypt for the second time.

Since Egypt has no water share agreement with Ethiopia, Egypt wants that agreement to be negotiated and agreed with a weak destabilised Ethiopia (exactly what they did to Sudan in 1959). By now Egypt should know “how Ethiopia is strongly founded “and its resilience to come out of crises. Despite the sudden and untimely death of PM Meles Zenawi who championed the concept of Ethiopian Renaissance and started the GERD and the internal instabilities that Ethiopia faced during the last year, the construction of the dam was not stopped for a fraction of a second. Now Ethiopia is already stable and is getting prepared for more rapid economic growth.

Since Egypt has no water share agreement with Ethiopia, Egypt wants that agreement to be negotiated and agreed with a weak destabilised Ethiopia (exactly what they did to Sudan in 1959). By now Egypt should know “how Ethiopia is strongly founded “and its resilience to come out of crises. Despite the sudden and untimely death of PM Meles Zenawi who championed the concept of Ethiopian Renaissance and started the GERD and the internal instabilities that Ethiopia faced during the last year, the construction of the dam was not stopped for a fraction of a second. Now Ethiopia is already stable and is getting prepared for more rapid economic growth.

Egypt’s concern of loss of ground as the main historical geopolitical player in the region to Ethiopia both from Africa, Middle East and Global perspective is also a bitter bill for Egypt to swallow and digest. I do not think Egypt should be emotional and concerned about the rising of Ethiopia which is one of the old civilisations that rivals Egypt and kept its independence and uniqueness during the good and bad time. It is always going to be true that both Egypt and Ethiopia have an irreplaceable and complementary role to play for peace, security, economic integration and social development of the region.

Egypt’s concern of loss of ground as the main historical geopolitical player in the region to Ethiopia both from Africa, Middle East and Global perspective is also a bitter bill for Egypt to swallow and digest. I do not think Egypt should be emotional and concerned about the rising of Ethiopia which is one of the old civilisations that rivals Egypt and kept its independence and uniqueness during the good and bad time. It is always going to be true that both Egypt and Ethiopia have an irreplaceable and complementary role to play for peace, security, economic integration and social development of the region.

Due to Egypt’s standing strategy of securing the lion share of the water from the Nile river( under the pretext of ensuring water security) at the expense of more than 300 million people around the Horn of Africa, it has been obsessed in sabotaging the peace and stability of Ethiopia and Sudan over the years and as the result the whole of Horn/East of Africa has been unstable and remained one of the poorest regions in the world and major source of migrants to Europe and elsewhere. Since the mid of 20th century, this region has witnessed the death of millions of people, both because of war and famine, aggravation of poverty and wastage of scarce billions of dollars for a war that could have been used for development.

Egypt’s strategy of sustaining its water security through sabotaging and destabilising Ethiopia and Sudan is no more a relevant strategy for Egypt (it is a myth). Egypt needs more water reservoirs to be built both in Sudan and Ethiopia for sustaining its water security. Storing water in the deep Abbay Gorge is the most attractive option as it could store more water at lower cost and less evaporation loss and lower usage of water other than generating hydroelectric power by Ethiopia. However, Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt should negotiate and agree a win-win water share tripartite and bilateral agreements. Of course, all other Nile Basin countries like Uganda, Kenya, and South Sudan etc. should also agree with both Sudan and Egypt on how to share the White Nile water.

Whatever plot Egypt may try to sabotage and destabilise the main water supplier to the Nile “Ethiopia “and the main potential Nile water Consumer” Sudan” may not be effective now as Egypt is currently economically weak and facing serious external and internal terrorism and war threats. In addition, the main neighbours of Ethiopia, except Eritrea, that Egypt had been historically using as a proxy to destabilise Ethiopia are currently allied with Ethiopia as they are fully aware of the consequences of being manipulated and used by Egypt to conspire against their strategic neighbour. The Eritrean government that has made Eritrea an open-air prison for its citizens is also increasingly being rejected by its people and it will collapse in the very near future. Therefore, Egypt should be ready for a realistic negotiation based on mutual respect and sustainable peaceful co-existence with Sudan and Ethiopia.

It is expected that Ethiopia and Sudan are jointly ready to counter and defend themselves from any uncalled aggression from Egypt!

1. Recommendations

(i) For Egypt

• Stop destabilising Ethiopia and Sudan as a confidence building measure

• Be transparent and open-minded for discussion and be ready to negotiate a win-win water share agreement with both Ethiopia and Sudan

(ii) Ethiopia and Sudan

• Create a united front to counter and defend Egypt’s bad behaviour and habit (I think this is already in place)

• Negotiate with Egypt united and from strength knowing the fact that Egypt badly needs more upstream dams for water reservoir for its future survival.

(iii) Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt

• Work on a strategy to build more dams on the Abbay Gorge that could be used mainly as reservoir and hydroelectric power generation, except for emergency cases.

• If the Abbay Gorge alone could store seven years of Nile annual flow volume-go for it- but share the costs.

Of course, including the cost of GERD.

Following to the end of the second world war Egypt’s failure to integrate Eritrea to its territories, due to Emperor Haile Selassie’s superior diplomatic skills, the then Pan- Arab nationalistic President Nasser’s government turned to ethnic and religious subversion against Ethiopia. In 1955 Egypt began working for the instigation of an “Arab” revolution in the then autonomous Ethiopian province Eritrea, to that effect, hundreds of young Muslims from Eritrea, were invited to Cairo to study and enjoy special benefits. Although they were not native Arabic speakers, they absorbed the spirit of Arab revolution and adopted a modern Arab identity. There they also learned how to set up a modern guerrilla ‘liberation front’ and by 1959 they had finalised their training in Egypt and were ready to establish the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) and they returned to the Sudanese town of Kassala and become connected to the pro- Egypt Sudanese Al-Mirghaniyya movement. More concretely the ELF launched an open anti-Ethiopian revolt in Eritrea in 1961, claiming and propagating a fake Arab Eritrean identity.

“The Arabism of Eritrean People” remained one slogan of Nasserism to its end and to promote Eritrea’s liberation from Ethiopia, Nasser was also ready to help local Eritrean Christian Tigrians who resisted reunification with Ethiopia. In 1955, the prominent leader of Christian Tigreans in Eritrea, WaldeAb WeldeMariam, was invited to broadcast daily anti-Ethiopian propaganda on Radio Cairo and the Nasserist regime remained the main pillar of support for the Eritrean separatist movement until 1963. The myth of Eritrea’s Arabism, adopted and advanced by Eritrean Muslims, was to survive until 1980’s and the war in Eritrea that was instigated by Egypt lasted 30 years and caused untold human and financial loss both to Ethiopia and Eritrea. As of today, Eritrea is a de facto colony of Egypt and is being utilised as a proxy war front against Ethiopia and it is also the command post of those Ethiopian political groups who opted to ally with Egypt. Hundreds of Eritreans’ industries, hardworking and proud citizens and their children escape the prison and pariah government of Eritrea on daily basis facing any risk on their way.

No less significant was the issue of Nasserist influence on the Somali nationalists and beginning in the mid-1950s Nasserist policy, literature, and agents worked to enhance the anti-Ethiopian dimension of Somali nationalism branded it as “Greater Somalia”. The Somalis encouraged by the potential Egypt backing, claimed about one-third of Ethiopia’s territory and when they united and received their independence in July 1960 and joined the Arab League 1974, they continued to present a serious on-going challenge (two wars fought) to the integrity of the Ethiopian sovereignty until Somalia was disintegrated and engulfed by civil war in 1991. The disintegration of Somalia which has caused the scatter of Somalis throughout the world and death of millions of Somalis by war and famine and wastage of decades of nation building opportunity was a byproduct of the failed Egyptians destabilisation strategy of Ethiopia.

Similarly, after Egypt failed to stop the British from allowing Sudan to declare its independence from Egypt in 1956, it has been constantly interfering into the internal affairs of Sudan including the Sudanese army staged coup d’état in November 1958, overthrowing the civilian government of Abdullah Khalil which had uncompromised and hard negotiation position on the Nile river, in which Egypt friendly Gen. Ibrahim Abboud led the new military government.

The 1959 Nile water share agreement signed between Egypt and Sudan which gave the lion share to Egypt (78% to Egypt and 22% to Sudan on the net annual flow after deducting 10 billion cubic meters for evaporation loss) was agreed with Gen Abboud. Considering the fact that, the flow measuring point is deep in Egypt at the Aswan High dam and the annual hypothetical evaporation loss of 10 billion cubic meters, the share for Sudan is substantially lower than 22%. If the water share allocation was done taking into account “population size and arable land area” as factors, Sudan’s share should have been not less than 40%.

Though Egypt opposed the split of South Sudan from Sudan during the pre-independence conflict time, currently it is the main sponsor of the fragile and corrupt President Kiir government and is prolonging the suffering of the South Sudan people with the objective of getting a foothold near to Ethiopian border to sabotage Ethiopia.

We are also hearing saber-rattling of few bribed government officials from South Sudan and Uganda trying to finger point at Ethiopia in relation to its decision to build the GERD and the speedy ratification of the “The Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement” by its parliament.

The Zero-Sum game that has been played by Egypt to ensure its water security has become unsustainable, out of dated and irrelevant (it is a myth) for the following reasons:

Considering the above points, it is expected that Egyptian water security strategists and the Egyptians government covertly want the construction of more dams in Sudan and Ethiopia as far as their historical share is not significantly affected. They also know that dams built in Ethiopia along the deep Abbay River Gorge could only be mainly used for hydroelectric power generation with lower evaporation loss and lower construction cost per volume. Egyptians are also considering others sources of water such us linking the Congo River with the White Nile and digging the Jonglei Canal in South Sudan which is good ideas but difficult to implement.

Then what is the reason that Egypt has been too nervous and trying to destabilise Ethiopia and sabotage the completion of the Great Ethiopian Renaissance dam(GERD)?

The following could be the main reasons:

Due to Egypt’s standing strategy of securing the lion share of the water from the Nile river( under the pretext of ensuring water security) at the expense of more than 300 million people around the Horn of Africa, it has been obsessed in sabotaging the peace and stability of Ethiopia and Sudan over the years and as the result the whole of Horn/East of Africa has been unstable and remained one of the poorest regions in the world and major source of migrants to Europe and elsewhere. Since the mid of 20th century, this region has witnessed the death of millions of people, both because of war and famine, aggravation of poverty and wastage of scarce billions of dollars for a war that could have been used for development.

Egypt’s strategy of sustaining its water security through sabotaging and destabilising Ethiopia and Sudan is no more a relevant strategy for Egypt (it is a myth). Egypt needs more water reservoirs to be built both in Sudan and Ethiopia for sustaining its water security. Storing water in the deep Abbay Gorge is the most attractive option as it could store more water at lower cost and less evaporation loss and lower usage of water other than generating hydroelectric power by Ethiopia. However, Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt should negotiate and agree a win-win water share tripartite and bilateral agreements. Of course, all other Nile Basin countries like Uganda, Kenya, and South Sudan etc. should also agree with both Sudan and Egypt on how to share the White Nile water.

Whatever plot Egypt may try to sabotage and destabilise the main water supplier to the Nile “Ethiopia “and the main potential Nile water Consumer” Sudan” may not be effective now as Egypt is currently economically weak and facing serious external and internal terrorism and war threats. In addition, the main neighbours of Ethiopia, except Eritrea, that Egypt had been historically using as a proxy to destabilise Ethiopia are currently allied with Ethiopia as they are fully aware of the consequences of being manipulated and used by Egypt to conspire against their strategic neighbour. The Eritrean government that has made Eritrea an open-air prison for its citizens is also increasingly being rejected by its people and it will collapse in the very near future. Therefore, Egypt should be ready for a realistic negotiation based on mutual respect and sustainable peaceful co-existence with Sudan and Ethiopia.

It is expected that Ethiopia and Sudan are jointly ready to counter and defend themselves from any uncalled aggression from Egypt!

1. Recommendations

(i) For Egypt

• Stop destabilising Ethiopia and Sudan as a confidence building measure

• Be transparent and open-minded for discussion and be ready to negotiate a win-win water share agreement with both Ethiopia and Sudan

(ii) Ethiopia and Sudan

• Create a united front to counter and defend Egypt’s bad behaviour and habit (I think this is already in place)

• Negotiate with Egypt united and from strength knowing the fact that Egypt badly needs more upstream dams for water reservoir for its future survival.

(iii) Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt

• Work on a strategy to build more dams on the Abbay Gorge that could be used mainly as reservoir and hydroelectric power generation, except for emergency cases.

• If the Abbay Gorge alone could store seven years of Nile annual flow volume-go for it- but share the costs.

Of course, including the cost of GERD.

The views expressed in the 'Comment and Analysis' section are solely the opinions of the writers. The veracity of any claims made are the responsibility of the author not Sudan Tribune.

If you want to submit an opinion piece or an analysis please email it to comment@sudantribune.com

Sudan Tribune reserves the right to edit articles before publication. Please include your full name, relevant personal information and political affiliations.